Born in San Francisco in 1934, Yvonne Rainer began training as a modern dancer in her early twenties at the Martha Graham School of Contemporary Dance in New York City. By 1960 she was taking experimental workshops at Merce Cunningham’s nearby studio, where Robert Dunn was applying John Cage’s chance-based compositions to dance. The same year Rainer started choreographing her own work, and by 1962 she and several others had founded the Judson Dance Theatre. Though the troupe had disbanded by 1964, their performances at the progressive Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village gave rise to an influential new style that resisted the showy virtuosity of ballet in favor of more commonplace movements, such as walking, running, and speaking. Rainer developed a philosophy of performance that, like the minimalist ethos percolating simultaneously, eschewed hierarchy. No single element—moment, body part, form, person—should appear more important than any other. Moreover, spectacle, which generated detached and unengaged viewers, should be avoided. This approach can be found in Rainer’s choreography and several of her early films, such as the five-minute _Hand Movie_. This 1966 film features a single shot of the artist’s hand “dancing.” Because no finger moves without affecting the whole, the work becomes an elegant representation of the artist’s conception of how body parts or dancers affect one another.

In the same year, Rainer developed her seminal dance _Trio A_, which was first performed by her and two others in street clothes to the clatter of falling wooden spoons at the Judson Memorial Church. The five-minute piece departs from tradition in featuring constant, rhythmic movements structured like tasks and enacted without pause or climax (a performer falls in stages rather than collapses). It is also unlike theatrical dance in that it is mutable. It can be taught to anyone and by anyone and since its debut has been performed by Rainer and others in more than twenty different incarnations. Not only has it been presented alone but also as part of her larger work _The Mind Is a Muscle_ (1968), an evening-long multipart performance involving choreographed movements for seven dancers, props, text, and film.

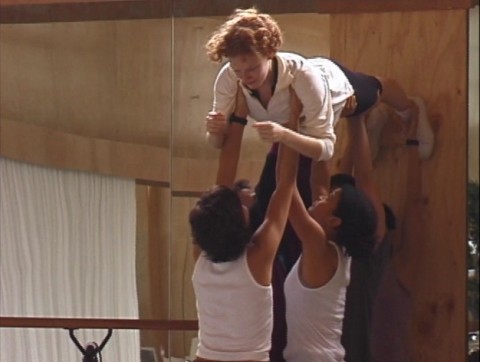

In 1975 Rainer moved away from dance and began concentrating instead on experimental feature-length films. Despite the shift, her critique of traditional notions of performance and the way that such representations function within society has become increasingly explicit. An example can be found in the recent film _After Many a Summer Dies the Swan: Hybrid_ (2002), which was produced two years after Rainer returned to choreography through several commissions by the Baryshnikov Dance Foundation for the White Oak Dance Project. One of these commissions formed the basis for this thirty-minute film, which mingles footage of rehearsals and a performance with historic images and texts. These elements come together in the film, whose title refers to a novel by Aldous Huxley which, among other things, reflects on cultural attitudes toward art. Rainer’s film delves into this territory by considering the role of aesthetics in fin-de-siècle Vienna, where tastes quickly changed as anti-Semitism and class disparity began to rise. With anguished music by Viennese composer Arnold Schoenberg setting the tone, the film frames the dancers’ movements in relationship to the story, which describes how once-radical works by artists such as Gustav Klimt were eventually co-opted by the bourgeois. At the conclusion of the film, a dancer strains to retrieve a microphone from atop a cardboard box and then recites a series of statistics about the disparity of pay between contemporary workers and executives. Immediately following, a text appears: “Redeem us from our isolation!” The phrase, which was a rallying cry of frustrated artists in Vienna a century ago, is an apt ending for Rainer’s piece and provides us with insight into her artistic philosophy. _—Kate Green_