Born in 1968 in New York, where he continues to live and work, American artist John Pilson has exhibited his photographs and videos in several solo exhibitions at the Centre Pompidou, Paris; the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; ArtPace, San Antonio, Texas; and P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center, Long Island City, N.Y., among other institutions. He received his B.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College in 1991, and upon receipt of his M.F.A. from Yale University in 1993, Pilson worked nights and weekends at Merrill Lynch as a graphic designer until 2000. The corporate office environment and conduct he observed during his employment offered fertile ground for the subject matter of his earliest videos. Pilson garnered attention in the late 1990s and early 2000s for works that featured individuals (often his friends and family members as actors) engaged in absurd and amusing behavior within office buildings. He examined how people define themselves through architectural spaces and how their characters emerge as a reaction to their environments. Due to the contemporary reality of lives overtaken by and dependent on employment, Pilson focused on how people inhabit their offices and play in stolen moments while supposedly at work. These singular acts ultimately reveal volumes on the nature of their inner anxieties, desires, and passions.

At the same time, Pilson defies viewer expectations of office conduct and redefines the workspace as a site for comedy and fantasy. In the black-and-white photographs that comprise Interregena (1999–2000), Pilson documents the downtime of the work environment. Among endless rows of cubicles, employees stare out windows or at their screens in search of excuses and ways to avoid work. Likewise, an accompanying video captures the transformation of this isolating environment into a setting of freedom and excitement, wherein a woman sings a Puccini aria, while her co-workers engage in a hurdle race. Above the Grid (2000) also features individuals that find escape from their oppressive surroundings. As a game of handball and a fight break out in an office, two businessmen sing doo-wop songs in the halls, restrooms, and elevators. Inexplicably, colorful balls later emerge out of nowhere to bounce down stairs and through corridors.

Pilson’s subsequent videos depict people connected by certain activities that are seemingly unaffected by the areas they inhabit. He captures spaces during conversations and events when individuals immerse themselves into their actions, memories, or imaginations and mentally extract themselves from their environments. In separate channels of Sunday Scenario (2005), three men joined by a conference call fanatically discuss sports at length. One man sits at the desk in his office, another man hikes through the woods with his dog, while the last one dressed in his pajamas lounges in his bedroom. The work demonstrates how technology creates a form of intimacy that seems independent of one’s surroundings.

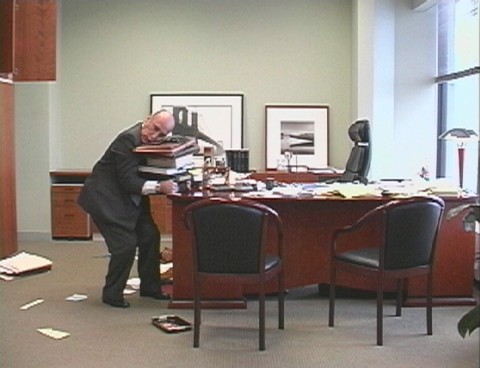

Mr. Pickup (2001) also features behavior inconsistent with its surroundings and viewer assumptions, and, like Pilson’s earlier works, it visualizes human moments within the walls of corporate spaces. The video, for which Pilson was awarded the Young Artists Special Prize at the 2001 Venice Biennale, begins in the well-appointed office of a lawyer played by Pilson’s father. As the man begins to gather his things and head to an important meeting, he enters an absurd downward spiral of epic proportions. For seventeen minutes, he is continuously unable to pick up the materials he needs. While his calls for help go unanswered, he remains determined through repeated attempts to gather his files and binders–objects ironically made to facilitate efficiency and organization. Finally, after his boss returns to chastise him and report that they have lost the deal, he gives up and walks out.

Pilson’s video is at once a comedic farce and a humanistic tragedy. Using slapstick gestures, it reveals the helplessness of a man unable to cope with the demands of the corporate world. His inability to meet the expectations of his firm counters stereotypes of the confident businessman and speaks to larger themes, especially after the 2008 financial meltdown. While the video appears empathetic to the subject’s vulnerability and ineptitude, it also suggests that his bungling is one of many cover-ups in the corporate world. In light of the ongoing revelations of illicit activities behind the closed doors of bankers, lawyers, and politicians, Mr. Pick-Up not only reminds us that humans are universally flawed, but also underlines how appearances can be devastatingly deceiving. —Kanitra Fletcher