Spontaneous future(s), Possible past

Beth Campbell

55 3/16 x 75 1/2 inches

Commission, Landmarks, The University of Texas at Austin, 2019

GPS: 30.277514, -97.735184

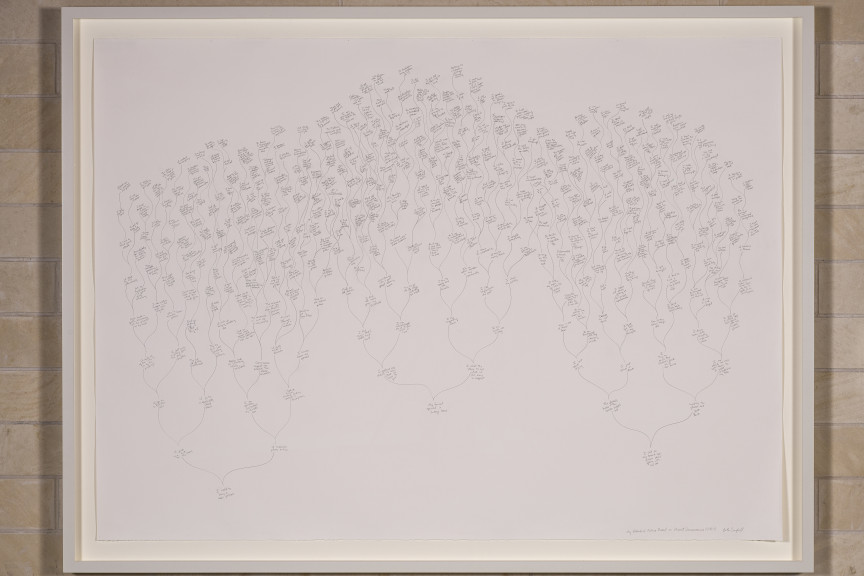

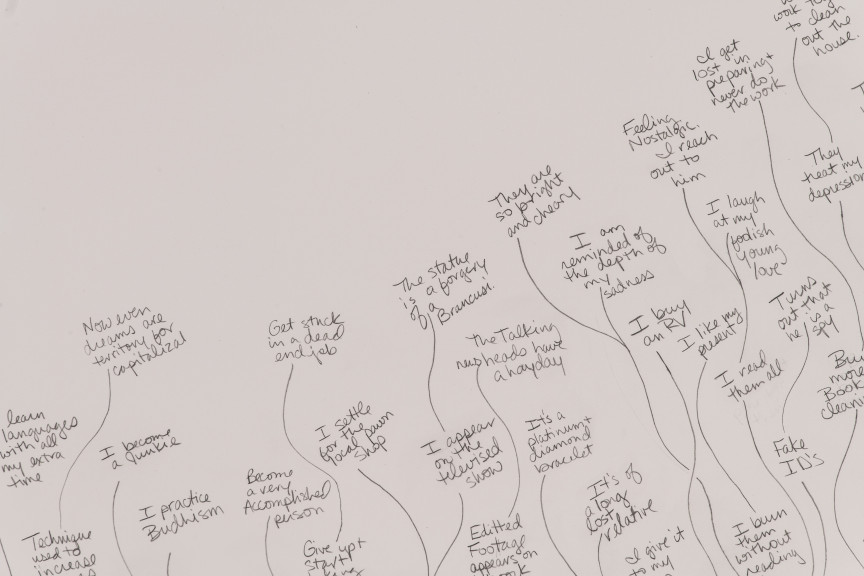

Delicately charting the human condition with all the gravity and humor of real life, Beth Campbell’s drawing and mobile for the Dell Medical School reveals the interconnectedness of shared experience. The site-specific commission Spontaneous future(s), Possible past is rooted in Campbell’s ongoing drawing series begun in 1999—My Potential Future Based on Present Circumstances. The series draws upon the artist’s interest in rhizomatic structures, circuit boards, and early virtual worlds in order to map imagined futures or parallel lives. Her text-based drawing for Landmarks, My Potential Future Based on Present Circumstances (1/13/19), is the first that Campbell has made in this series in a decade. It draws parallels to spontaneous future cognition, a newly developing branch of cognitive psychology that explores the random and involuntary thoughts that individuals have about their future.

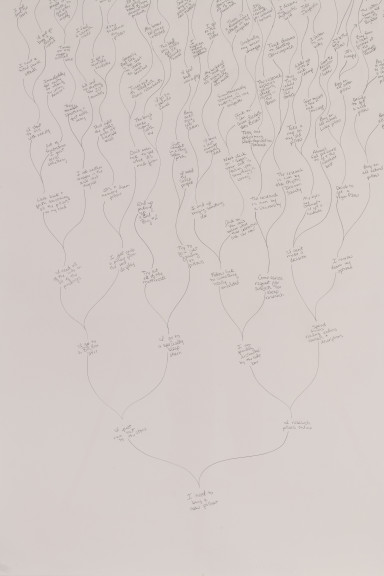

Campbell begins each work by considering a seemingly mundane or relatable moment from her everyday life—i.e. “I just sat on my brand-new glasses while getting into the car” or “I need to buy a new pillow.” She then uses gestural lines to diagram a flowchart of possible outcomes unfolding from the event, ranging from fantastic to tragic. Like neural networks, the drawings branch out in linear fashion, accumulating narrative tentacular strands that chronicle various possibilities resulting from choice or chance. The result simultaneously exposes parallel states of mind while questioning our relationship to the future.

Also on view at Dell Medical School and a companion to the drawing, Campbell’s mobile extends this drawing into three-dimensional space, expanding her thought process and hypothetical considerations into repeated forms that mirror one another like speculative visualizations of possibility. Referred to by the artist as a “[drawing] in space,” the mobiles are made by forging steel wires by hand. They mimic the twists and turns of complex structures such as the human nervous system, an arboreal root system, or social networks.

LEARNING AT HOME WITH LANDMARKS

Bring the Landmarks collection into your home-learning environment. Check out how you can engage with this work by browsing the learning resources featured on this page:

- View Photo Gallery - Click on the arrows on the sides of the image above to to view images of the work. Spend time on each photo and examine details carefully as if you were with the work in person.

- Play Audio Guide - Select “Play Audio Guide” in the upper right corner to hear a short audio guide about the art and gain a deeper understanding of its meaning.

- View Videos - Select “View Videos” to watch a 3-minute video with the artist and to understand their process.

- Activity Guides - Choose the activity guide below best suited for young learners in your home.

Still have questions or want to share your Learning at Home with Landmarks experience with us? Keep the conversation going by tagging Landmarks on social media.

ACTIVITY GUIDES

Spontaneous future(s), Possible past

Beth Campbell

Subject: Moveable Mobile

Activity: Create a mobile using only wire and string

Materials: Wire hanger; yarn, ribbon, or string; pipe cleaners

Vocabulary: Mobile, balance, line, shape

Artist Beth Campbell makes mobiles out of lightweight materials like wire that hang from ceilings. They are so light they move with just a small breeze. When the air moves the wires, the shape of the entire sculpture changes.

How did the artist make this sculpture?

The sculpture moves with a light breeze, without touching it, what else could make the sculpture move?

Using a wire hanger as your base, twist, tie, knot, and loop yarn, string, or pipe cleaners to create a mobile. You can use different materials, or the same material like artist Beth Campbell. Try to loop or tie ends of strings onto other strings and watch your mobile grow longer and longer!

Hang your mobile on a door frame or a fan and watch it sway in the breeze!

Beth thinks of this sculpture as a drawing floating in space. She used the drawing in this lobby to help her design the sculpture.

What is similar about the drawing and sculpture? What is different?

Mobile - A sculpture that is hung from the ceiling and moves freely in the air

Balance - An arrangement of shapes and colors where no part is more important than another

Line - A straight or curved mark that does not connect

Shape - A form like a circle, square, or triangle

Spontaneous future(s), Possible past

Beth Campbell

Subject: 3D Drawing

Activity: Create a wire sculpture and embellish it with beads and string

Materials: Flexible, thin wire; ribbon or yarn; beads; pencil and paper

Vocabulary: Sculpture, drawing, shape, line, embellish

Beth Campbell uses wire to make large works of art that hang from the ceiling. She likes to use wire because she can bend it in any direction, the way a pencil on paper makes different lines. Her mobiles look like 3D drawings floating in the air.

Can you imagine how the artist made this?

What tools did she use?

Does the sculpture remind you of something you’ve see in nature?

How would the sculpture move if a breeze blew through the building?

Using a pencil and paper draw a simple line drawing. Try a flower, fish, or something else you find in nature. This is the model for your sculpture.

Bend, curl, and shape the wire to look like your drawing. Twist smaller pieces of wire onto the main shape to add detail.

When your 3D drawing is complete consider adding beads, yarn, or ribbon to embellish with color.

Beth Campbell used the drawing found in this lobby as the inspiration for the mobile.

Once you’ve completed your own 3D drawing, look back at Spontaneous future(s), Possible past and consider how it was made.

Sculpture - A 3D work of art

Drawing - A work of art where marks are made on paper

Shape - A form like a circle, square, or triangle

Line - A straight or curved mark that doesn’t connect

Embellish - To decorate with colorful items like beads, glitter, or string

Spontaneous future(s), Possible past

Beth Campbell

Subject: Word Patterns

Activity: Create a Potential Future Drawing

Materials: Pencil, large sheets of paper

Vocabulary: Hypothetical, composition, movement, flow

Artist Beth Campbell uses the title Potential Future Drawing to describe drawings that map hypothetical events. First, she thinks of a something simple that happened to her that day; like “I sat on my new glasses.” She writes this down, then thinks of potential next steps. She draws a line out from that phrase and writes the next action. Then she imagines what would happen if she did one action verses the other, creating hypothetical stories. What results is a cluster of potential storylines. Her drawings show how complex our minds and thoughts are even when thinking of something simple.

Can you find the start of her drawing?

Can you trace the start all the way to one potential ending?

Step back, what shape does the entire drawing take?

Does the shape look like something from nature?

Create your own Potential Future Drawing!

Take a large sheet of paper (or tape together several small sheets to create one large sheet) and think of something that happened to you today. It doesn’t have to be something special; the simpler the better! Write what happened down at the bottom of your paper. Then imagine 2-3 different actions you can take as next steps. Draw a line for each and write each one down. Then from each new action, think of what you would do next. Draw a line for each and write each one down. Continue this pattern until your drawing grows across the entire page.

Download the activity guide to see an example.

Beth used this drawing to inspire the shape of her mobile across the lobby.

Does Campbell’s drawing grow more in one direction than another? Does yours? What shape does your drawing look like? Does it look like something from nature?

Hypothetical - An imagined scenario or event

Composition - The plan, placement, or arrangement of the shapes and colors in a work of art

Movement - An arrangement of shapes and colors that gives the feeling of motion and guides the viewer’s eyes around a work of art

Flow - The direction an element in a drawing takes that helps our eyes view a drawing

MORE INFORMATION

Can the future be predicted perfectly, and how do predictions determine and constrain what happens next? According to artist Beth Campbell (b. 1971), we do a lot of extrapolating about the future based on our present circumstances. Her use of diagrams raises questions about what diagrams are and how they function. Diagrams can imply automation (whether or not the automation is done by hand, by clockwork, or by computer). The trouble with automation is not artificial intelligence—I can’t prove that I’m not an android, even to myself. Any algorithm, any recipe, is a set of instructions that are necessarily inscribed in the past and that represent past states of human doings. A recipe for a boiled egg, for example, is indicative of the ways we’ve been boiling eggs so far. What happens when there are a million eggs boiling all at once? All the unintended (and intended) consequences of that small action get hugely amplified.

The trouble with automation is that it’s based on the past, and having a lot of it means that the past is eating the future. It might be good to imagine how things aren’t inevitable. Artist Beth Campbell takes on that task.

Through drawings, sculpture, and architectural interventions, Campbell explores the interconnectedness of our world— how we perceive and experience our surroundings and how we are altered by them. She choreographs spaces, crafts uncanny objects, and maps thought to augment viewers’ experience of reality and challenge preconceived notions of the experience and self.

Campbell began to chart thoughts and ideas in early, text-based drawings Everything (1997) and Web Drawing of Me (1997); both diagrammatic works map the various roles Campbell performed for herself and for others. The commission for Landmarks is part of a series Campbell began in 1999, My Potential Future Based on Present Circumstances. The series maps possible futures and gives physical shape to streams of consciousness; each drawing branches out from a single occurrence in her everyday life into a host of outcomes ranging from fantastic to abysmal. After exhibiting a drawing from this series alongside work by Mark Lombardi in Friendly Strangers (1999) at Galapagos in Brooklyn, the two artists developed a friendship from which many have drawn connections and comparisons. Conceptually, the two artists are concerned with different subject matter: while Lombardi documents the abuse of power from financial and political powerhouses, Campbell creates a more intimate portrayal while speaking of the larger world. Similar to artists like Charles Ray and Tim Hawkinson, in this series Campbell uses herself as a subject without the constraints of portraiture or other traditional representations.

Early on Campbell sought the subtle, mesmerizing work of Veji Celmins, who painstakingly replicates the physical world through drawing and sculpture as a vehicle to connect with something bigger. Further inspiration comes from Swiss artists Peter Fischli and David Weiss, who highlight the humor and absurdity of everyday objects while also underscoring how they help us form deep and direct connections to the world. Campbell’s installations embrace the clumsiness of objects—exploring how they interact with one another and how they influence us. In Everything I Own(scape) (1997), Campbell created a large canyon-like, striated installation made from the objects with which she comingled. Her Never Ending Continuity Error (2004) plays with the viewer’s capacity for self-reflection. In it, four bathroom stalls are presented without mirrors in all except the farthest, creating the effect of an infinity mirror. The reflection from the distant mirror is delayed and out of reach.

Campbell’s research is eclectic and connects ideas in philosophy and psychology, the presence of the past, the possibilities of futures, and the influence of technology. dah-dah- dah-dah-dit, dah dah-dah-dah, di-di-di-di-dit (2018) supports the notion that the past is all around us by physically combining two seemingly distant, pre-Internet histories that have come to inform our current time. Titled “nine to five” in Morse code, images from an 1880s telegraph office, with traces of its female operators, collide with scenes from the 1980s movie 9 to 5, set after the women take over.

Spontaneous future(s), Possible past, 2019

Perhaps the biggest question that arises when you think about Campbell is, How flexible are things? Which is another way of asking the question, Can things be different? The commission for Landmarks, Spontaneous future(s), Possible past: My Potential Future Based on Present Circumstances (1/13/19), consists of two parts: a drawing and a mobile. The drawing is the first that Campbell has made in the series My Potential Future Based on Present Circumstances in a decade. The personal voice behind the text departs from the taut vocabulary of conceptual art while appropriating its tropes. Her drawing practice is quiet and meditative, culling inspiration from the seemingly insignificant moments in life. Fundamentally, she is concerned with the human conscious and how we understand our relationship to ourselves, others, and our surroundings. She looks both internally and to the world around her in order to create opportunities to see the commonalities of our experiences.

Campbell’s diametric drawings serve as studies for delicate, three-dimensional mobiles that expand her thought process and hypothetical considerations into repeated forms that mirror one another like speculative possibilities. Handmade of steel rod and wire, the artist refers to them as “drawings in space.” They mimic the twists and turns of complex structures such as the human nervous system, an arboreal root system, or social networks. Delicately charting the human condition with all the gravity and humor of real life, Campbell’s work reveals the interconnectedness of shared experience.

The flow-chart, evolutionary-tree-like mobile structure for Landmarks looks a bit like a diagram that came to life, with a kind of energy of its own rippling through it. The structure has a charming conversation with gravity. Dangling, oscillating, wiggling—a structure whose nodes are light and loose allows for a certain movement; not defying gravity, for sure, but certainly having a lively, syncopated conversation with it.

How flexible are things? Really flexible. Only consider quantum theory. There is a basic quantum of movement, a shimmering or oscillating without being pushed, a vibrating without mechanical input of any kind. This is why we can have the other kinds of movement, because things are already mobile this way. As Campbell puts it, “When the viewer moves around the mobile and sees the lines overlap (witnessing the parallax shift), lines look like they shimmer or like a non-patterned moiré effect.”

Because movement is a basic part of how things are, basic and baked in, novelty can happen. There is a kind of “wiggle room” in which change can happen, and this feature of things is deeply part of a difference between what they are and how they appear.

Now let’s think about things that are bigger than us. We tend to think of these things as oppressive and imprisoning. But that’s not necessary at all. Campbell’s mobile implies additions to itself, just like family trees—it could be bigger. A small piece of the structure repeats what the form is like at a larger scale. What happens at a small region of it may affect what happens somewhere else, and what happens to the object as a whole may affect its smaller parts. But these effects are not linear. A system with that many nodes must be chaotic. What happens at one scale may look very different from what happens at another.

Being an ecological being and part of the biosphere seems like something we know how to talk about already—we are part of nature, we are all Earthlings…funnily enough, almost every concept we have tended to employ, until recently, is prone to drastically not saying anything about what it’s really like, and that’s because human culture has been hard at work producing untenable differences between the human and the nonhuman, in every conceivable way.

What we need is an artist who makes art out of the very idea of constructing a world—oh look, there is one.

Huge systems with lots of variables, like climate, do tend to be chaotic—hence the image of a butterfly flapping its wings in Tokyo causing a tornado in Texas. A hyperobject is anything so vast that relative to the way something else is experiencing or taking the measure of it (or whatever), it’s “massively distributed” in space and time, in such a way that it’s very difficult or even impossible to point even to parts of it, let alone the whole thing. One consequence is that beings such as humans or Kentucky Blue Grass always find themselves caught in a number of overlapping hyperobjects, which can themselves be members of even larger ones.

A thing isn’t completely swallowed up in the bigger thing of which it’s a part, at least not in this case. If you believe ecological things such as meadows are made of lots of different lifeforms and other stuff and that they can overlap with other ecological things such as hedgerows and climate, you have to believe that heaps of things are just as real as the things that comprise them. The belief that wholes are more or less real than parts of them means that we are stuck in a theological, metaphysical way of talking about them.

When we say, “the whole is always more than the sum of its parts” we are contributing to this mode, even if we think we’re atheists. We are saying that some things are more real than others. The whole is more real than the part, which is why the way to have a part is to totally dissolve the part in itself.

We should admit that if a whole like a meadow is just as real as a part like a flower (which can also be a whole consisting of lots of things such as chloroplasts and micorhizzae, symbiotic lifeforms), it is “less” than the sum of its parts. The wholes in which we find ourselves are finite and fragile just like you are. They can be changed. We are not swallowed in them.

Hyperobjects really defeat traditional and oppressive ideas about omnipotence, omnipresence, and omniscience—that they are possible, and that they are desirable. They are wonky wholes that can overlap with other wholes, fragile constructs that no matter how physically large and intimidating, lack the infinite power that we tend to lend such things. They can be changed. They can be eliminated.

So the worlds we live in—and the words trees live in, and office chairs—are intrinsically tattered and perforated. The world phenomenon altogether is cheap and lossy like a badly recorded mp3. There is wiggle room for new stuff to happen. The genius of Beth Campbell is that she allows for this basic wiggling; she lets it talk about itself in her work. The future wiggles in the form of a fragile entity, all the dangling pieces. The past was how it was put together. To be a thing at all is to be a mobile in which what you are and how you appear circle around one another, not touching.

When I was a child, floating above my bed was a mobile consisting of three witches.

Timothy Morton is the Rita Shea Guffey Chair in English at Rice University in Houston, Texas. His research focuses on object-oriented thought and ecological studies. He has written extensively on philosophy, ecology, literature, music, art, architecture, design and food, with recent publications including Being Ecological (2018); Humankind: Solidarity with Nonhuman People (2017); and Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence (2016). In 2014, Morton gave the Wellek Lectures in Theory–an annual series presented by internationally distinguished theorists at the University of California, Irvine. He has collaborated with Björk, Jeff Bridges, Jennifer Walshe, Olafur Eliasson, Haim Steinbach, and Pharrell Williams, among others.

Grabner, Michelle. “Beth Campbell.” In Responses to Calder: Mobiles in Contemporary Art. Germany: Kunsthalle Wilhelmshaven and Kerber Art, 2014.

Kulkielski, Tina. Beth Campbell. Following Room. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2007.

Lasota, Catherine. “The Art of Drawing with Text.” Electric Literature, September 9, 2017.

Saltz, Jerry. “Repeat Performance.” Village Voice, October 9–15, 2002, 52.

Stewart, Amy Smith. Beth Campbell: My Potential Future Past. Ridgefield, CT: The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, 2017.

Visit Beth Campbell's website.

Landmarks commissioned two new works by artist Beth Campbell for Dell Medical School. Her drawing and corresponding mobile mimic the twists and turns of complex structures such as the human nervous system, an arboreal root system, or social networks. Delicately charting the human condition with all the gravity and humor of real life, Spontaneous future(s), Possible past reveals the interconnectedness of shared experience.

Funding for Spontaneous future(s), Possible past was provided by the capital improvement project for Dell Medical School. Landmarks would like to thank to the following:

Leadership

Darrell Bazzell and Financial and Administrative Services

Andrée Bober and Landmarks

Douglas Dempster and the College of Fine Arts

Gregory Fenves and the Office of the President

Clay Johnston and Dell Medical School

Landmarks Advisory Committee

James Shackleford and the Office of Capital Planning and Construction

Campus Master Planning Committee

David Rea and the Office of Campus Planning and Project Management?

Project Team

Nisa Barger, project manager, Landmarks

Andrée Bober, curator and director, LandmarksBeth Campbell, artist

Ron Pauley, Page Sutherland Page

Brock Rindahl, Capital Planning and Construction

Vaughn Construction

Vault Fine Art Services

Catherine Williams, Silver Lining Art Conservation

Special Thanks

Kathleen Brady Stimpert, deputy director, Landmarks

Glenn Deaver, Dell Medical School

Deb Duval, event coordinator, Landmarks

Lisa Jones, Dell Medical School

Emma Kirks, operations, Landmarks

Logan Larsen, intern, Landmarks

Jennalie Lyons, development, Landmarks

Marla Martinez, Financial and Administrative Services

Maggie Mitts, collections management, Landmarks

Timothy Morton, curatorial contributor

Ricardo Puemape, Dell Medical School

Danny Lane Russell, design, Landmarks

Stephanie Taparauskas, development, Landmarks

Kate Werble, Kate Werble Gallery

Catherine Zinser, education, Landmarks