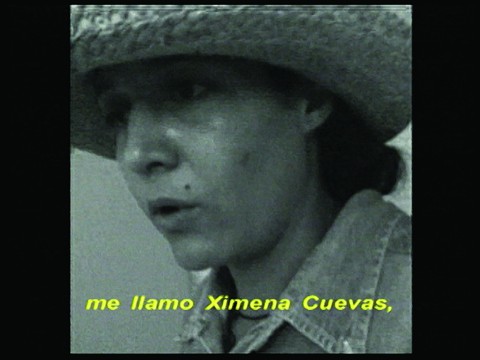

A career in video art seems as though it was inevitable for Mexico City–based artist Ximena Cuevas. As a child she watched her artist father, José Luis Cuevas, draw and make images come to life. And as a teenager living in Paris, she cut class to watch four films a day for two years straight. When she moved back to her hometown of Mexico City at the age of sixteen, she worked at the Cineteca National where she “repaired” films, meaning she literally cut out the parts of the filmstrips that had been censored. Cuevas went on to study film at the New School for Social Research and Columbia University in New York in 1980. For the next ten years, she would work on more than twenty films by directors who include Konstantinos Costa-Gavras, John Schlesinger, and John Huston, in positions ranging from assistant director to artistic director, continuity director, and lighting double.

Cuevas purchased a video 8 home camera in 1991 and left the mainstream film world. She embarked on her own career in video art, developing an experimental, expressionistic style influenced by her fascination with secrets, artifice, and the melodrama most often seen in telenovelas. By 2001, she had become the first Mexican video artist to be represented in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Her videos have been shown at the Guggenheim Museums in New York and Bilbao, New York Film Festival, Sundance Film Festival, Hammer Museum, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, and the Brooklyn Museum, among other venues. She has been the recipient of grants from the Rockefeller, MacArthur, and Lampiada Foundations; the Mexican National Endowment for Culture and the Arts; and Eastman Kodak’s Worldwide Independent Filmmaker Production Fund. In 2017, Cuevas was nominated for a Mexican Academy Award for her editing work on the documentary Beauties of the Night.

Cuevas’s early work includes Bleeding Heart (1993), a music video parody starring Astrid Hadad. She portrays a woman who has had her heart broken by her romantic partner in a surrealist montage set to the tune of a love ballad. Victims of Neoliberal Sins (1995) is a satire of the corrupt presidency of Carlos Salinas de Gortari performed in the manner of Mexican film cliches, and Half Lies (1995) is an experimental documentary in which Cuevas responds to media manipulation, the Americanization of Mexico, and the Zapatista uprising. Framed by a drive through Mexico City, Cuevas weaves together street scenes, schoolbook illustrations, and imagery of President Ernesto Zedillo, Zapatistas, and 1940s movie stars in a biting critique of the vagaries of modern Mexican political and popular cultures. Paper Bodies (1997) is a surrealist visualization of jealousy in the disintegration of a lesbian relationship.

Contemporary Artist (1999) hilariously captures the realities of anxiety felt by artists making their way in the contemporary art world. Through a handheld camera at the fictitious institution MOCO in Mexico City, Cuevas sees John Hanhardt, senior curator of film and media arts at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, in the bookstore. Her voiceover expresses her shock, which quickly turns into panic as she deliberates how to introduce herself. The shaky view of the camera lens also conveys her nervousness, as the recording plays forward and in reverse several times, complementing her switch from Spanish to English, which she believes is more "trendy."

Cuevas runs to the bathroom to prepare an introduction and rehearse how to approach Hanhardt. Demonstrably flustered and overwhelmed, she repeats “My name is…,” “I am an artist…,” and “My project is…” She pants and barely gets out her own name, but she does mention the names of other curators and critics as a way to elevate her status in Hanhardt’s mind. Finally ready to approach him, the recording fast forwards, returning to the store, but the curator is no longer there. Cuevas’s camera searches the store, other floors in the museum, and outside on the sidewalk, as she hopelessly calls out his name, to no avail.

While humorous, Contemporary Artist conveys the intense rawness and realness of Cuevas’s scenario and her emotions. It comments on the power dynamics of the art world, such as the often-imbalanced relationship between curators and artists, who desire their attention. Notwithstanding the inspiring nature of art seen in museums, there are startingly different, less desirable situations and interactions that take place behind the scenes for the work to be exhibited. Moreover, artists in Mexico and other countries of the Global South can feel even more pressure in a US–dominated contemporary art world, hence Cuevas’s frenzied reaction to the New York–based curator. As in much of her work, she does exaggerate the drama in the video, but in doing so, sheds light on the performance necessary to be a Contemporary Artist in the real world. —Kanitra Fletcher