The madness that lies beneath our mediated reality and mannered society surfaces in the hands of Rokni Haerizadeh (b. 1978, Tehran, Iran). His most recent artwork appropriates found imagery—photographs and videos of galas, riots, murders, and parades from international news agencies—and transforms it into dreamlike expressionistic scenes. Figures become animal-human hybrids and headless or grotesque forms that suggest a kind of dual humanity. Haerizadeh examines the idea that as we indulge in lavish, choreographed rituals, we also succumb to sordid, animalistic tendencies, both of which are exploited in mass-media spectacles.

Haerizadeh recognizes the ironic outcome of this exploitation, when events become normalized. As a commentary on the familiarity of extravagant weddings, funerals, and other ceremonies, as well as that of protests, insurrections, and other uprisings, Haerizadeh’s artwork renders those occasions strange and surreal. In the ink and watercolor drawings and animations of his _Fictionville_ series (2009–ongoing), one observes the televised death of Iranian protestor Neda Agha-Soltan or the broadcast marriage of Prince William and Kate Middleton, but in fantastical form.

Haerizadeh’s early artwork hinted at the development of this latest phase. He painted subtle satires of social events, including _Typical Iranian Wedding_ (2008) or _Typical Iranian Funeral_ (2008). These works often consist of chaotic, densely populated scenes that also reveal segregated, dichotomous structures—male and female, public and private—hidden within. Thus, they suggest underlying tensions and anxieties as well as the possibility of subversion.

These and other works were exhibited in high-profile international venues, garnering attention that prevented Haerizadeh and his brother, the artist Ramin, from returning to Iran while traveling from Paris in 2009. At that time, they learned they were under official suspicion of the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance, and several of their works were confiscated from the home of a Tehran collector. Facing possible imprisonment, they arranged for temporary residence in Dubai, where they continue to live and work today.

Perhaps due to Haerizadeh’s status in exile, _Fictionville_ was inspired by Iranian playwright Bijan Mofid’s musical play/political critique _Shahr-e Qesseh_, or _City of Tales_. Although the parable was written in 1968 as a reproach to pre-revolutionary Iran, for Haerizadeh, its animalizing tactic—the characters include camels, monkeys, elephants, and the requisite ass— remains suitable. However, rather than imparting moral lessons, in Haerizadeh’s series all the players are implicated.

Instead of the various forms of bourgeois culture and consumerism displayed in Richard Hamilton’s 1956 Pop art collage _Just What Is It that Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?_, Haerizadeh’s video of the same title (2010–11) takes the media coverage of the 2009 Iranian demonstrations as its subject matter. The heads of both the demonstrators and news anchors become those of pigs, bears, cats, and so on as they engage in and are surrounded by absurd, violent behavior. Nonetheless, Haerizadeh shares with Hamilton a thematic concern for the spectacular, yet shallow, nature of mass media and popular culture, which viewers impassively consume. The layers, textures, and contours of the work encourage us to see the cultural, historical, and emotional dimensions these events comprise.

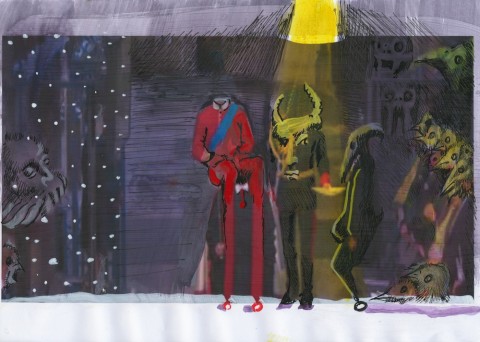

Also a part of the _Fictionville_ series, Haerizadeh’s animated video _Reign of Winter_ (2012) takes the identically titled poem by Akhavan Sales as its inspiration. “It describes the bitter-cold cruelty of winter, and the colorless existence of those left outside at the mercy of the elements… it reflects the spirit of our times.” Fittingly, throughout the action, his animation features snowlike white dots falling along the perimeter of the frame. Along with intermittent swirls of grey clouds, howling skulls that emerge from the trees, and the pulsating forms of stop-motion technique, Haerizadeh’s film offers a chilling replay of the royal wedding of Kate and William.

It follows two headless figures, one in a white wedding dress with a veil composed of a trail of black ink spots and the other in a red uniform that morphs into breasts, genitals, and legs of a horse. These odd forms, along with an array of animal-human characters, go from the ceremony at Westminster Abbey, to the carriage ride down the Mall, to the balcony of Buckingham Palace. Haerizadeh’s bestial, shape-shifting imagery gives an account of the festivities that is diametrically opposed to its coverage in the press.

In so doing, his macabre, mocking take on the wedding emphasizes not only the hysteria of the occasion but also the (literal) manipulation of the media. We need not see the actual faces of the participants, as the heads of animals and decapitated bodies point to the ways we see them, or their representation. In this sense, Haerizadeh suggests we did not watch the wedding of Kate and William in April 2012, we watched its portrayal in the media, which was just as constructed and choreographed as _Reign of Winter_. _—Kanitra Fletcher_