Despite his short lifespan of thirty-five years, Gordon Matta-Clark was a highly productive artist who would become a major influence on generations of artists and architects. Matta-Clark was born in 1943 to the American artist Anna Clark and the Chilean Surrealist painter Roberto Matta. He lived in France, Chile, and New York, and earned his BA in architecture at Cornell University before his untimely death from pancreatic cancer in 1978. While at Cornell, Matta-Clark showed little interest or ability in his chosen major and spent most of his time with students in the studio art department. By assisting them with the installation of the _Earth Art_ exhibition in 1968, he also met visiting artist Robert Smithson whose interest in entropy and rejection of art commodification would make a lasting impression on Matta-Clark after his move to New York City in 1969.

During the 1970s, he helped turn SoHo into a vibrant artist community. With a group of artists, he organized 112 Greene, an exhibition space that featured his _Garbage Wall_ (1971), a performance piece and prototype for a homeless shelter. That same year, he also collaborated with artist Carol Goodden to open Food, a restaurant that was managed and staffed by artists. The open kitchen and exotic ingredients turned dining into a performative event, making the space a popular hangout.

Over the next few years, Matta-Clark produced a large number of drawings, some of which he created using a cutting technique to make geometric designs. By 1974 his practice was oriented around "building cuts" in which he sawed and carved abandoned buildings to create sculptural objects. As the buildings were slated for demolition, Matta-Clark's completed structures were temporary. Thus, he filmed and photographed each process to later exhibit his documentation along with fragments of the building themselves.

Among those projects, which he collectively termed Anarchitecture, is _Bingo_ (1974), a work in which he removed the facade of a condemned house along Love Canal in Niagara Falls and moved the resultant walls to Artpark in Lewiston, New York. Matta-Clark also made _Conical Intersect_ (1975) for the Biennale de Paris by cutting two large cone-shaped volumes into two seventeenth-century townhouses. For _Day's End_ (1975), he removed part of the floor and roof of Manhattan's Pier 52 to create a "sun and water temple" that resulted in a lawsuit filed (and eventually dropped) by the City of New York. Lastly, _Circus_ (1978), his final project, was large circular holes carved into the walls, ceilings, and floors of a four-story brick building next to the first MCA Chicago building. These and other projects by Matta-Clark reflected his interest in the inner workings and spaces under or beyond visible surfaces, or rather barriers, as he viewed them.

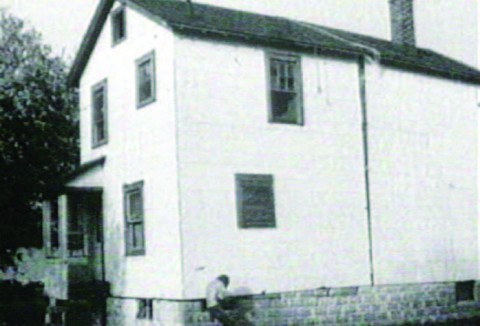

According to gallerist Holly Solomon, Matta-Clark's works also were subversive, unexpected, and "always tinged with a sense of danger and performance." It also was Solomon who presented him with the two-story wood frame house at 322 Humphrey Street, Englewood, New Jersey, that would become _Splitting_ (1974), his first large-scale and most celebrated Anarchitectural project. The work existed for only three months before its demolition, and using a handheld camera Matta-Clark filmed each phase of the project from start to finish. With the help of other artists, he sliced two parallel vertical lines through the house and jacked the house up and off its foundation to lower the back half slightly, causing the initial divisions to widen and open the structure to natural light. Sunrays then filled the interior of the structure, giving the documentary a disorienting, kaleidoscopic effect that is emphasized by the twists and turns of the camera.

Like many artists of the late 1960s and 1970s, Matta-Clark was concerned about the dehumanization of the modern world, and _Splitting_ (literally) sheds light on the imposed order of American bourgeois culture. By cutting and angling the house, he disrupted the planned layout of the suburban landscape, exposing the interior rooms and layers as metaphors for systems of social division and compartmentalization. In a sense, Matta-Clark tore through spatial and structural barriers to reveal social and cultural obstacles as well as those between human and natural environments. Gently tipped and slimly cut, the house allowed visitors to enter and view the natural world from the inside. Such an experience generally would be restricted or even impossible for occupants, yet it also seems long overdue, as _Splitting's_ lingering, penultimate image of a stoic tree suggests. _—Kanitra Fletcher_