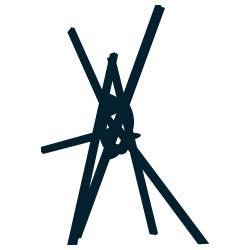

Clock Knot

Mark di Suvero

498 × 260 × 420 inches

Photography not permitted

Purchase, Landmarks, The University of Texas at Austin, 2013

GPS: 30.289671,-97.736162

Mark di Suvero is one of the most important sculptors of his generation. As a student, he was deeply engaged in studying and writing poetry and was attuned to music, from Bach to jazz. Once he began to pursue sculpture, di Suvero found an outlet for his explorations in other fields that intrigued him, including architecture, mathematics, science, engineering, poetry, and languages.

Grounded in abstract expressionism, which emphasizes the direct expression of emotion through line and color, di Suvero was energized by the spaces of New York City, especially those being torn down for “urban renewal.” From the refuse, he pioneered a new form of sculpture in which wooden beams chained together in outward-leaning constructions declared the physical forces that held them in check. The works engage space in an unprecedented manner, and this focus on space has remained a central goal throughout di Suvero’s career. In 1967 he began to build large-scale sculptures with a crane, using steel I-beams and other industrial materials. Learning to use a crane offered di Suvero a new mode of working, but it was one in which the process of composing the sculpture remained at the core of his artistic practice.

The heroic sculpture Clock Knot exemplifies the power of art to transform public locations. Walking around the work produces constantly changing views, and moving under it offers another experience of the sculpture and its space. The crossed I-beams and circular “knotted” center of Clock Knot suggest a giant clock face with a horizontal “hand” extending to the left. But as one moves around the sculpture, what had been read as a vertical beam shows itself to be one leg of an inverted V-form. Is it a clock or not/knot? Clock Knot is a work of poetry and power. As visitors pass through its space looking at the sky and feeling the exuberant lift of the sculpture, their imaginations will play with its visual and verbal suggestions.

ACTIVITY GUIDES

Clock Knot

Mark di Suvero

Subject: Balance

Activity: Creating a sculpture that balances

Materials: Acrylic paint (optional), chopsticks, pencils, or Popsicle sticks; adhesive tape, glue, string, or twist ties

Vocabulary: Angle, balance, crane, lift, vertical

Mark di Suvero often uses large steel beams to create his sculptures. His sculptures are so large that he has to use a crane to lift the beams and set them in place. Di Suvero works in New York City and is influenced by the construction of massive skyscrapers. In his works, he is interested in balance and lift. Clock Knot balances well on four beams, despite its precarious angles. It is called Clock Knot because it looks a little like a giant clock face with a clock hand that extends from the center.

Do you think the sculpture looks balanced? How difficult do you think it was for di Suvero to achieve balance?

Walk around the sculpture. How does the sculpture change? Walk under the sculpture. What is it like looking up from underneath the sculpture?

Do you think this sculpture looks like a clock? Why or why not?

Collect a variety of objects such as chopsticks, pencils, or Popsicle sticks. Try to balance the objects together using adhesive tape, glue, string, or twist ties. When you are done, paint your sculpture with acrylic paint if you like.

Angle - two lines that extend from the same point

Balance - to keep steady

Crane - a machine for raising, shifting, and lowering heavy weights

Lift - lifting up or elevating; an elevation of the spirit

Vertical - positioned upright, like a flagpole, and opposite of horizontal

Clock Knot

Mark di Suvero

Subject: Balance and lift

Activity: Creating a sculpture with balance and lift

Materials: Acrylic paint (optional), sticks, wooden beams, or metal rods (such as discarded curtain rods or rebar)

Vocabulary: Balance, crane, lift

Mark di Suvero was born to Italian parents in Shanghai in 1933. He grew up in San Francisco. After attending college, he moved to New York City and settled in lower Manhattan. The area, near the Fulton Fish Market, was rapidly changing. Buildings were constantly being torn down while new ones were being raised. Di Suvero began collecting materials that he found at the demolition sites, including large wooden beams. He then chained the beams together to create sculptures. Throughout his career, he has been interested in balance and lift, perhaps as a reaction to his early years watching the creation of some of Manhattan’s most impressive skyscrapers.

Clock Knot suggests an enormous clock face with a clock hand extending from the center. However, upon walking around the sculpture, the viewer discovers that the clock hand is really part of an inverted V. The word “knot” in the title then becomes a play on words, referring both to the tangle in the center of the sculpture and the fact that this is “knot/not” a clock. The sculpture is so massive and heavy, di Suvero had to use a crane—as he does for all of his large sculptures—to move the beams into position. He then carefully constructed the sculpture so that it would be stable, despite its precarious angles.

Like Clock Knot, the structural framework of a skyscraper is made from steel beams. In terms of the purpose and construction of these two forms, what similarities or differences can you identify?

Do you think the sculpture looks balanced? How difficult do you think it was for di Suvero to achieve balance?

Walk around the sculpture. How does the sculpture change? Walk under the sculpture. What is this experience like?

Collect such objects as sticks, wood beams, or metal rods (such as discarded curtain rods or rebar). Try to balance the objects together in a sculpture with a vertical movement. You may choose, like di Suvero, to use chains to keep the pieces together. You might also use bungee cord or rope. When you are done, paint your sculpture with acrylic paint if you like.

In a 1983 interview with Architectural Digest, di Suvero explained his process: “When you pick up a large weight with a crane, you need a sense of its center of gravity. This is something dancers understand: the way you can control a weight by shifting its center. Working near the limits of a crane’s capacity, it’s very easy to make a mistake. A cable can snap; the whole rig can tip over. So the process is delicate—like playing a violin. I try to get some of that sense of balance into my work. Just because a sculpture is big, it doesn’t have to be rigid.”

Tony Smith’s Amaryllis is also made from steel and then painted a solid color. How are Amaryllis and Clock Knot similar or different? How do you think the material affected the building of each of the sculptures? Which sculpture looks heavier? Why do you think Smith and di Suvero painted their sculptures?

Balance - to keep steady

Crane - a machine for raising, shifting, and lowering heavy weights

Lift - lifting up or elevating; an elevation of the spirit

Clock Knot

Mark di Suvero

Subject: Angles

Activity: Creating a drawing with different angles

Materials: Ruler, paper, and pencils, crayons, or markers

Vocabulary: Angle, crane, sculpture, vertical

Mark di Suvero’s sculpture has many angles. An angle is made when two lines come from the same point. An angle is like a triangle with one of the lines missing. Di Suvero made this sculpture by lifting very heavy steel beams with a crane. A crane is a large machine with an arm and a kind of hook. It can move very heavy objects. Cranes are used to make big buildings.

How many angles can you count in the sculpture?

Walk around the sculpture. Does it look different from the side? From the back? From the front?

This sculpture is called Clock Knot. Do you think it looks like a clock?

Ask the child to use a ruler to make one long vertical line. Then ask him or her to make another line that crosses the first line. How many angles does the child see now? Can he or she make triangles from the angles by adding another line? Ask the child to continue to make intersecting lines. Suggest that the child use different colored pencils, crayons, or markers to fill in the triangles when he or she finds them.

Angle - two lines that extend from the same point

Crane - a machine for raising, shifting, and lowering heavy weights

Sculpture - a work of art that has height, width, and depth

Vertical - positioned upright, like a flagpole, and opposite of horizontal

MORE INFORMATION

Mark di Suvero is one of the most important sculptors of his generation. As a philosophy major at the University of California, Berkeley, in the mid-1950s, di Suvero was deeply engaged in studying and writing poetry and was also attuned to music, from Bach to jazz. Once he began to pursue sculpture as an undergraduate, however, di Suvero found his calling as well as an outlet for his explorations in other fields that intrigued him, including architecture, mathematics, science, and, ultimately, structural engineering.

Born of Italian parents in Shanghai in 1933, di Suvero spent his youth in San Francisco. After his Berkeley education and a period of work, he moved to New York in 1957, settling in the vicinity of the Fulton Fish Market in lower Manhattan. That area near the Brooklyn Bridge as well as the building at 79 Park Place became gathering points for his friends from the California School of Fine Arts, who successively gravitated to New York and with whom he established and maintained a communal, cooperative gallery on the top floor of the Park Place building from 1963 to 1964. Relocated to Greenwich Village in 1965, the Park Place Gallery continued to operate through 1967.

Grounded in abstract expressionism, with its emphasis on the direct expression of emotion through line and color, di Suvero and his friends were energized by the spaces of the city, which were changing about them as buildings in this area were being torn down for “urban renewal.” From the refuse found at demolition sites, di Suvero pioneered a new form of sculpture in which wooden beams, chained together in outward-leaning constructions, declared the physical forces that held them in check. Upon seeing these works in a 1960 exhibition at the Green Gallery, critic Sidney Geist responded, “From now on nothing will be the same.” Often compared to the bold gestures of abstract expressionist painter Franz Kline (see Black and White, No. 2, Blanton Museum of Art), di Suvero’s sculptures engaged space in a far more active way than had earlier sculpture. That focus on space remained a central goal when in 1967 he began to build large-scale sculptures with a crane, using steel I-beams and other industrial materials, as in Clock Knot.

In 1960 di Suvero was paralyzed in an elevator accident, and his recovery is a testament to his determination and commitment to his art. During his year in a rehabilitation hospital he taught art to his fellow patients, and for di Suvero this sharing of art as a “springboard for the spirit,” as he says, would become a central goal for his artistic practice. Learning to use a crane offered the artist a new mode of working, but it was one in which the process of composing the sculpture remained at the core: instead of drawing on paper, he was drawing in space with his steel beams. One of di Suvero’s heroes was Alexander Calder, who had incorporated wind-driven motion into his hanging “mobiles.” For di Suvero, as for Calder and other kinetic artists, the presence of motion and time in their work was a means of aligning it with Einstein’s theories of relativity and space-time. While motion has been a central element of many of di Suvero’s sculptures since the 1960s, equally important for him is a viewer’s participation in the work—moving around to capture its changing vistas, and, when the work has moveable parts, swinging or banging on it (some works even sport mallets for the purpose). He hopes to reawaken the child in each of us by an encounter with his sculpture, reigniting the sense of wonder that is often lost to us as adults.

But di Suvero’s purpose goes beyond individual viewers: he is an idealist with a strong political and social vision of art’s role in improving the world. Di Suvero’s activities have ranged from Vietnam War protest via art (his 1966 Peace Tower in Los Angeles) or self-imposed exile in France (1971–74) to forming a foundation to support young artists. He has also converted an abandoned landfill adjacent to his “Spacetime Constructs” studio in Queens, New York, into the Socrates Sculpture Park, which has transformed the landscape along the East River and offers young sculptors a place to exhibit large-scale works. Di Suvero’s impressive body of sculpture—so energetic and muscular and engaged with space as well as contemporary social realities—eludes easy stylistic labels and represents a vital alternative to the minimalist sculpture associated with the 1960s artists Tony Smith and Donald Judd.

Clock Knot, 2007

Di Suvero’s titles, such as Molecule, Nova Albion (from a poem by William Blake), Mahatma (for Gandhi), The “A” Train, and E=MC2, document the range of sources from which he draws inspiration. The title for the forty-one-foot Clock Knot was arrived at differently, however. He held a contest to name the work, and a poet from New York suggested the winning title, which suits the work perfectly and adds a dimension of wordplay. From one vantage point, the Clock Knot’s crossed I-beams and circular “knotted” center do suggest a giant clock face with a horizontal clock “hand” extending to the left. (Steel beams connect 11:00 and 5:00, 12:00 and 6:00, and 1:00 and 7:00.) But as one moves around the work to the left or right, what had been read as a vertical beam from 12:00 to 6:00 shows itself to be one leg of an inverted V form. Suddenly, is it a clock or not/knot? Walking around Clock Knot produces constantly changing views, and moving under it creates yet another experience of the sculpture and its space. Historically, sculpture was an object to be looked at, usually on a pedestal, not something one viewed from underneath. Clock Knot, by contrast, offers a totally new visual and physiological experience.

Di Suvero learned structural engineering largely through experimentation. For his early sculptures, he often invited children from the neighboring housing projects to come to his studio and play and jump on his works. Even with years of experience, constructing a sculpture is still an ad hoc process for him, as he explained to Carter Ratcliff in a 1983 interview in Architectural Digest:

When you pick up a large weight with a crane, you need a sense of its center of gravity. This is something dancers understand, the way you can control a weight by shifting its center. Working near the limits of a crane’s capacity, it’s very easy to make a mistake. A cable can snap, the whole rig can tip over. So the process is delicate—like playing a violin. I try to get some of that sense of balance into my work. Just because a sculpture is big, it doesn’t have to be rigid.

Think of Clock Knot as a multi-ton dancer who has alighted on the lawn of the Chemical and Petroleum Engineering building, demonstrating the principles of balance and force that apply equally in engineering and in dance. Clock Knot is a work of poetry and power, which will have those who pass through its space looking at the sky and feeling the sculpture’s exuberant lift at the same time their imaginations play with its visual and verbal suggestions.

Linda Dalrymple Henderson is the David Bruton, Jr. Centennial Professor in Art History in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Texas at Austin. In addition to her books The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art (1983; new ed. 2013) and Duchamp in Context: Science and Technology in the Large Glass and Related Works (1998), she organized the 2008 Blanton Museum exhibition Reimagining Space: The Park Place Group in 1960s New York, which included works by Mark di Suvero.

Baker, Alyson, and Ivana Mestrovic, eds. Socrates Sculpture Park. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

Di Suvero, Mark. Mark di Suvero: Dreambook. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.

Musée d’Art Moderne et d’Art Contemporaine. Mark di Suvero: Retrospective, 1959–91. Nice, 1991.

Rosenstein, Harris. “Di Suvero: The Pressures of Reality.” Art News 65 (February 1967): 36–39, 63–65.

Simon, Joan. “Urbanist at Large.” [interview] Art in America 93 (November 2005): 156–65, 193–94.

Storm King Art Center. Mark di Suvero at Storm King Art Center. Mountainville, NY, 1996. Essay by Irving Sandler.

Whitney Museum of American Art. Mark di Suvero. Org. by James K. Monte. New York, 1975.

The monumental sculpture Clock Knot by Mark di Suvero exemplifies the power of public art to transform the university’s landscape. Its installation coincided with the opening of the exhibition Reimagining Space: The Park Place Gallery Group in 1960s New York at the Blanton Museum of Art from 28 September – 18 January 2009.

The installation was initially made possible with a generous contribution from the College of Fine Arts and a loan from the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery. The acquisition of the sculpture was funded by the School of Engineering’s capital improvement project in 2013.

Landmarks would like to thank:

Leadership

Andrée Bober and Landmarks

Pat Clubb and University Operations

Douglas Dempster and the College of Fine Arts

Landmarks Advisory Committee

William Powers and the Office of the President

David Rea and the Office of Campus Planning

Ben Streetman, Gregory Fenves, and the Cockrell School of Engineering

Bill Throop and Project Management and Construction Services

Samuel Wilson and the Faculty Building Advisory Committee

Project Team

Andrée Bober, curator and director, Landmarks

Mark di Suvero and Spacetime Constructs

Cliff Koeninger, architect

Roy Lee, rigging

Lowell McKegney, chief installer

Ricardo Puemape, Project Management and Construction Services

Nicole Vlado, project manager, Landmarks

Special Thanks

Kurt Heinzelman, poet

Linda Dalyrmple Henderson, curatorial contributor

Ivana Mestrovich, Spacetime Constructs

Beth Palazzolo, administrative coordination, University Operations

Paula Cooper Gallery

In 2008 artist Mark di Suvero held a contest at Socrates Sculpture Park to name this sculpture. He selected the winning entry, a proposed title by writer Elaine Bleakney—Clock Knot.

With the unveiling of Clock Knot that same year, poet and scholar Kurt Heinzelman wrote an ekphrastic poem to commemorate the sculpture. Below is his composition, Clock Knot Square Dance.

---

CLOCK KNOT

SQUARE DANCE

Kurt Heinzelman

The knees are bent so

that the hands of time

may touch for once their

own toes allemande

left in your own back-

yard, right then left

around the ring Off

speed the fire trucks of

morning to an up-

town derelict book

depository

to practice their high-

rise rescues swing your

corner with the old

left hand, then meet your

partner, promenade

home At the base of

the green knoll where it's

been turning after-

noon all day, a café

nestles among the

statues, the general

rubbish, like a piece

of topiary,

offering sunshiny

burritos and a

studious ease do-

si-do with the one

below then twirl a

left star once more round

Now the engineers

of evening, who know

more than anyone

how everything

that can fly out of

someone's hand sooner

or later will, are

closing up their lap-

tops and closing down

the wireless halls of

Chicago brick and

in no time at all

have begun to square

dance together in

their high domed labs then

turn and roll away

with a half sashay

while the moving hands

of an orrery

upon the table,

made all of glass, trace

the faint tinnitus

of the eldritch stars.

after the construction called

"Clock Knot" by Mark di Suvero